I am not the intended audience for William Goldman’s The Princess Bride. Likely you’re not either, as you’re reading this on Tor.com. We read fantasy. We love books about heroes and villains and giants and princesses. We are not so cynical that we have to be coaxed into a story about true love and a wicked prince and a masked pirate.

Goldman isn’t a fantasy writer. He’s a literary writer, and his imagined readers are literary readers, and he wrote The Princess Bride with no expectation that it would fit on my shelves between Parke Godwin and Lisa Goldstein. It’s possible he’d be slightly embarrassed if he knew he was rubbing shoulders with them, and he’d be happier to see his work set between William Golding and Nadine Gorimer. He wrote The Princess Bride in 1973, after Tolkien, but before genre fantasy was a publishing phenomenon. And it’s not genre fantasy—though it (or anyway the movie) is part of what has shaped genre fantasy as it is today. Goldman’s novel is a swashbuckling fairytale. I think Goldman wanted to write something like a children’s book with the thrills of a children’s book, but for adults. Many writers have an imaginary reader, and I think Goldman’s imaginary reader for The Princess Bride was a cynic who normally reads John Updike, and a lot of what Goldman is doing in the way he wrote the book is trying to woo that reader. So, with that reader in mind, he wrote it with a very interesting frame. And when he came to make it into a movie, he wrote it with a different and also interesting frame.

I might be a long way from Goldman’s imagined reader, but I am the real reader. I love it. I didn’t find the book when it was new, but years later. I can’t even answer the question of whether I read the book or saw the film first. I read part of the book multiple times and then I saw the film multiple times and then I read all of the book.

I first came across The Princess Bride in Spider Robinson’s anthology The Best of All Possible Worlds (1980). This was a very odd theme anthology, where Robinson selected a bunch of stories from writers and asked the writers to choose another story by somebody else to go with that story. I still own the volume, and without going to the other room to pick it up I can tell you that what it has in it is Heinlein’s “The Man Who Travelled in Elephants” (which is why I bought it, because in 1981 I really would buy a whole anthology for one Heinlein story I hadn’t read) and an excerpt from The Princess Bride and a Sturgeon story and… some other stuff. And the excerpt from The Princess Bride is Inigo Montoya’s backstory, told to the Man in Black at the top of the cliffs, and then the swordfight. And I read it, and I wanted more, and when I went to look for it I discovered that the book had never been published in the UK and not only could I not own it but interlibrary loan was not going to get it for me. Reader, I wept. (Nobody has this problem now. The internet is just awesome. No, wait, fifteen year olds without credit cards and with non-reading parents still have this problem all the time. Fund libraries! Donate books!)

Then in 1987 when I was all grown up (22) and working in London. I saw teaser posters for the movie. First, they were all over the Underground as a purple silhouette of the cliffs, and they said “Giants, Villains. Wizards. True Love.—Not just your basic, average, everyday, ordinary, run-of-the-mill, ho-hum fairy tale.” They didn’t say the name of the movie or anything else, but I was reasonably excited anyway. I mean giants, villains, wizards… hey… and then one day I was going to work and changing trains in Oxford Circus and I came around a corner and there was the poster in full colour, and the name was there, and it was The Princess Bride that I’d been waiting to read in forever, and now it was a film.

You may not know this, because the film is now a cult classic and everyone you know can quote every line, but it wasn’t a box office success. But that wasn’t my fault. I took fourteen people to see it on the opening night. I saw it multiple times in the cinema, and after the first run I went out of my way to see it any time it was shown anywhere. (This was after movies but before DVDs. This is what we had to do.) My then-boyfriend said scornfully that it was the only film I liked. (That isn’t true. I also liked Diva, and Jean de Florette and American Dreamer.) Also in 1988 Futura published the book in Britain (with a tie in cover) so I finally got to read it. Sometimes when you wait, you do get what you want.

The book wasn’t what I expected, because I’d seen the film and the film-frame, but I had no idea about the book-frame, and so came as a surprise, and it took me a while to warm to it. It was 1988, and genre fantasy was a thing and my second favourite thing to read, and this wasn’t it. Anyway, I wasn’t the reader Goldman was looking for, and it was all meta and made me uncomfortable. I think Goldman may have meant to make me uncomfortable, incidentally, in his quest to make the adult reader of literature enjoy a fairytale he may have wanted to make the child reader of fairytales re-examine the pleasure she got out of them. Goldman would like me to have a little distance in there. I might not want that, but he was going to give it to me nevertheless. I didn’t like it the first time I read it—I would have liked the book a lot better without the frame—but it grew on me with re-reading. Thinking about the meta in The Princess Bride made me a better reader, a more thoughtful one with more interesting thoughts about narrative.

What Goldman says he is doing, in giving us the “good parts version” of Morganstern’s classic novel, is giving us the essence of a children’s fairytale adventure, but in place of what he says he is cutting—the long boring allegories, the details of packing hats—he gives us a sad story of a man in a failing marriage who wants to connect with his son and can’t. The “Goldman” of the frame of the novel is very different from Goldman himself, but he embraces the meta and blurs the line between fiction and fact. There are people who read the book and think that Morganstern is real and that Florin and Guilder are real places. How many more are deceived by the way Goldman talks about “himself” and his family here, the way he says the Cliffs of Insanity influenced Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the very clever way he leads in to all that, so that by the time he’s almost confiding in the reader the reader has already read between a lot of lines? It’s all plausible detail, and it does lead one to question the line between fictional and real.

The frame gives the imagined reader what the imagined reader is imagined to be used to—a story about a middle-aged married man in contemporary America who is dealing with issues related to those things. We also have the relationship between the child Goldman and his immigrant grandfather, as well as the relationship between the adult Goldman and his family. And it’s all sad and gives a sour note—and that sour note is in fact just what the story needs. The sourness of the frame, the muted colours and unhappiness in “real life,” allows the sweetness, the true love and adventure of the fairytale within the frame to shine more brightly, not just for the imagined reader but for all of us.

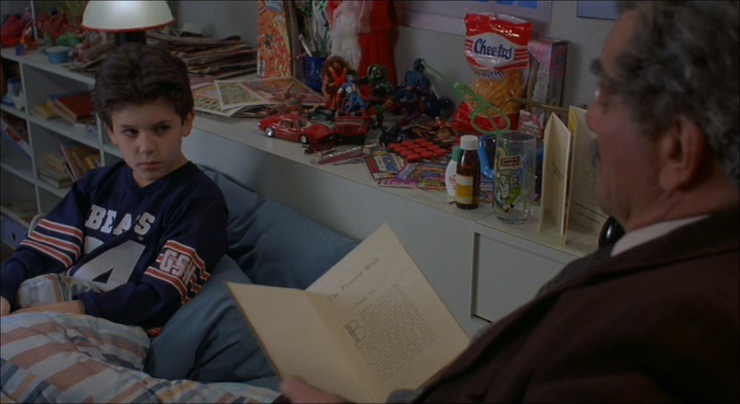

The frame of the movie—the grandfather reading the story to the reluctant grandson—is less sour, but more meta. The grandson is used to challenge the story “Hold it, hold it!” and thus to endorse it where it isn’t challenged. He stands in for the reader (“Who gets Humperdinck?”) and as he is lulled into enjoying it, so is the imagined reader/viewer. This frame also allows for the kind of distancing that brings us closer—the constant reminders that this is a story let us get caught up in it.

But while the frame of the novel keeps reminding us of unhappiness and mundanity in the real world to show the fairytale more brightly, the frame of the movie keeps reminding us of the real world in the context of narrative conventions. The novel frame blurs the line between fiction and reality by putting a dose of reality into the fiction, and the movie frame does it the other way around—it reminds us we are being told a story, and it comments on what a story is, and can be. I frequently quote it when I am talking about tension balancing—“She does not get eaten by eels at this time”—and “You’re very smart, now shut up” is my shorthand for the way of approaching stories that get in the way of appreciating them, whether as a reader or a writer. (Writers can get into their own light in that exact way.)

Goldman is interested in showing up the narrative conventions of revenge, true love, quests and so on, but also the way of telling a story. The kid approaches the story like the most naive kind of reader—he wants to know what’s in it that he likes, are there any sports? And then he dismisses the romantic element—“Is this going to be a kissing book?” He thinks he knows what kind of story he wants, and then he gets this one—he’s being seduced by the old-fashioned story from the old country, the grandfather’s story. And his presence shows us things about suspense, and involvement—it’s not just the reversal where it goes from the him condescending to allow the grandfather to tell the story to begging him to keep on telling it, it’s that when the story cheats us with Buttercup’s dream sequence he is there within the movie to express our outrage. And we can laugh at him and condescend to him—he’s a kid after all—but at the same time identify. We have all had the experience of being children, and of experiencing stories in that way. Goldman’s movie frame deftly positions us so that we simultaneously both inside and outside that kid.

I often don’t like things that are meta, because I feel there’s no point to them and because if I don’t care then why am I bothering? I hate Beckett. I hate things that are so ironic they refuse to take anything seriously at any level, including themselves. Irony should be an ingredient, a necessary salt, without any element of irony a text can become earnest and weighed down. But irony isn’t enough on its own—when it isn’t possible for a work to be sincere about anything, irony can become poisonous, like trying to eat something that’s all salt.

Brust is definitely writing genre fantasy, and he knows what it is, and he is writing it with me as his imagined reader, so that’s great. And he’s always playing with narrative conventions and with ways of telling stories, within the heart of genre fantasy—Teckla is structured as a laundry list, and he constantly plays with narrators, to the point where the Paarfi books have a narrator who addresses the gentle reader directly, and he does all this within the frame of the secondary world fantasy and makes it work admirably. In Dragon and Taltos he nests the story (in different ways) that are like Arabian Nights crossed with puzzle boxes. But his work is very easy to read, compulsively so, and I think this is because there’s always a surface there—there might be a whole lot going on under the surface but there’s always enough surface to hold you up. And like Goldman, he loves the work, and he thinks it’s cool, and he’s serious about it, even when he’s not.

Thinking about narrative, and The Princess Bride, and Brust, and Diderot, made me realise the commonalities between them. They’re all warm, and the meta things I don’t care for are cold and ironic. All these things have irony (“Anyone who tells you different is selling something…”) but the irony is within the text, not coming between me and the characters. There’s no “Ha ha, made you care!” no implied superiority of the author for the naive reader, there’s sympathy and a hand out to help me over the mire, even when Goldman’s telling me the story I didn’t want about “his” lack of love, he’s making me care about “him,” in addition to caring about Inigo and Wesley. Nor is he mocking me for believing in true love while I read the fairytale, he’s trying his best to find a bridge to let even his imagined cynical reader believe in it too.

You can’t write a successful pastiche of something unless you love it.

To make a pastiche work, you have to be able to see what makes the original thing great as well as what makes it absurd, you have to be able to understand why people want it in the first place. You have to be able to see all around it. This is why Galaxy Quest works and everything else that tries to do that fails in a mean spirited way. The Princess Bride is the same, Goldman clearly loves the fairytale even when making fun of it and that makes it all work. The characters are real characters we can care about, even when they’re also larger than life or caricatures. Because Goldman has that distancing in the frame, the loveless life, the cynicism, within the actual story we can have nobility and drama and true love. We could have had them anyway, but even his imagined reader can have them, can accept the fire swamp and the Cliffs of Insanity because he’s been shown a pool in Hollywood and a second hand bookstore, can accept Florin because he’s been told about Florinese immigrants to New York.

The Princess Bride in both incarnations has a real point to what its doing and cares about its characters and makes me care, including the characters in the frame. And you can read it as a fairytale with a frame, or a frame with a fairytale, and it works either way.

And I might not be the intended audience, but I love it anyway.

This article was originally published September 25, 2014

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published a collection of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections and ten novels, including the Hugo and Nebula winning Among Others. Her most recent book is My Real Children. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.

This movie was my first official date as a young teenager.

Readers love this book so much that at least once a year someone walks into my bookstore and asks for a copy of Buttercup’s Baby. True love!

You should ask Mike Scott about this, because he has the UK first edition, with the red and black text, hardback; the book the Interlibrary loan system told you doesn’t exist. Macmillan 1975. The Internet describes it as ‘very scarce’. I have lots of Goldman and like it all moderately, but I loved this book immoderately. The fiim was therefore a crushing disappointment to me because of the changed backstory and other book into film issues; though I like it well enough on its own terms now.

Reading The Princess Bride out loud was one of the all-time greatest successes in our family’s Reading Out Loud programme, too.

Love the book, love the story. And it never ceases to amaze me that it is a favorite here at geekdom. I did not know that it was not a box office success. But, I know it has become a cult simply because when someone says “As you wish” or “My name is Inigo Montoya, you killed my father, prepare to die,” we all know who was being quoted.

Sadly, they don’t make movies like this anymore. It has to be a blockbuster like Star Wars or Iron Man for it to get a remake. Nevertheless, I will always remember the movie and the book.

My son is going to be 14 in a few days. He hasn’t yet understood why I inflicted this movie on it even though he loves it just the same. I hope that I am still in this world when he does understand why…

Ah, the book…the “good bits” version of The Princess Bride…I remember buying this book when I was 14 or so, seduced by the cover and the blurb…already an experienced genre reader…and being so bitterly disappointed by the meta-narrative that I didn’t finish it! Which was very rare for me at that point in my reading career. Talk about not being the reader for this book!

But I remembered the book fondly, in a weird way, precisely BECAUSE of my argument with the meta-narrative. Actual argument – I remember my justification for giving up on it being – “well, I WANT the whole ‘Princess Bride’ you talk about – not just the ‘good bits’ – I WANT the economics and the political satire and all the stuff you’re leaving out because YOU think it’s boring!” It didn’t help to remind myself that there was no actual ‘unabridged’ “Princess Bride”! And it made me realize that I was, finally and proudly, a throwback to the 19th century in my tastes – no kiddie klassic ‘good bits’ versions for me, ever! Bring on the asides, the side-excursions, the ranting and the politics! Oh, yeah, and the action, too.

Sadly, my experience with the book made me resist the movie for years, and the more my friends kept quoting it at me the more I kept resisting, until finally I was just too old for that kind of pointless contrarianism and I gave up and watched it, and, like the rest of the world, found it thoroughly delightful.

Gosh darn it, now you’re making me want to go dig up the book and read it, now that I’m an adult! Who knows, maybe I’ll finally find it delightful as well, after all these years. Round of applause!

Like Jo, my introduction to The Princess Bride was Spider Robinson’s The Best of All Possible Worlds. I don’t know how many times I re-read that extract with the climb up the Cliffs of Insanity and the sword fight at the top. I spent at least three or four years keeping an eye out for the book, and eventually found a mint copy of the American paperback in the second-hand book shop I lived above. Still feels more like to book found me, than I found it. The whole book lived up to what I had been expecting from the extract, especially since the framing section, with it’s own search for a copy of the book mirrored my own search of years for a copy. Of course, that turned out to be less than a year before the movie tie-in edition appeared everywhere. I actually missed the cinema release, can’t recall why, but that turned out to be lucky, as my first time watching it was at the Eastercon, in the infamous projection sequence which showed the middle reel three times, once in reverse.

My introduction to The Princess Bride was having it read aloud to me by my first boyfriend, which was pretty much entirely awesome.